Forgotten millet should solve India’s rice problem, ‘resistant to diverse climate’

Originally published in NOS News of the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (NOS)

06 December 2023, Netherlands: It is not nutritious, wastes scarce water and contributes to climate change. Yet rice is on the plates of most Indians every day. An age-old, but forgotten crop should provide a solution: millet. At India’s initiative, the United Nations declared 2023 as the ‘Year of Millet’.

Kuldeep Singh can endlessly list different varieties of millets. He heads a gene bank in southern India, where the seeds of tens of thousands of variations of all millet varieties are kept in cold storage. These were collected in 144 countries. The collection serves as an insurance policy for a future with climate change, unknown diseases and population growth. Singh beams when he talks about the qualities of millet.

“Finger millet, for example, is very rich in calcium. No other crop has as much calcium as this. And most of these millet varieties can withstand a diverse climate, less water, high temperatures. Pearl millet, for example, is a crop that can withstand temperatures above 45 degrees can grow. No crop can do that.”

Logical replacement

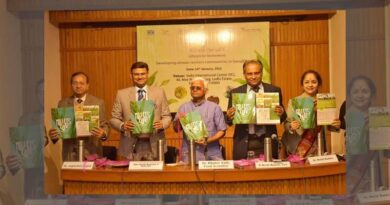

The gene bank is part of the agricultural research institute for an arid and tropical climate, ICRISAT, which is working with India and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to promote millet worldwide. Dr. Jacqueline Hughes is the Director General.

“Where water becomes scarce, millet is a logical replacement for rice,” she says. “Rice needs an average of 2,500 liters of water per kilo to grow. For millet it is only a quarter of that amount.”

Rice is also extremely vulnerable to climate change. Due to rising temperatures, seasonal fluctuations and extreme weather, production per hectare is declining. Rice production also contributes to climate change. It emits more methane gas than other crops. The Economist wrote earlier this year that rice production produces twelve percent of global methane gas emissions and one and a half percent of all greenhouse gases, which is comparable to the aviation sector.

In practice, it is quite a challenge to replace rice. Not just in India, but throughout Asia, where 90 percent of the world’s rice is grown. This was also encouraged for decades. In India, rice is one of the main crops that is subsidized by the government and purchased with guaranteed minimum prices for the public distribution system. Since the last major agricultural revolution, rice has provided food security.

Rice alone is not very nutritious. Although hunger is almost non-existent, malnutrition is a major problem in India. Rice also contributes to the relatively common occurrence of diabetes in India.

Population growth

But with a growing population, the demand for rice as a kitchen favorite will only increase, and so will all the rice-related problems. The government is already supporting projects on a small scale to stimulate the demand for millet. This is also the case in the state of Telangana, in a number of remote villages about a seven-hour drive from the ICRISAT campus and gene bank. Here, millet is on the menu at childcare centers sponsored by the government.

“We started a pilot in 2017 for around 5,000 women and children,” says Priyanka Durgalla, a scientist at ICRISAT involved in the project. ICRISAT also helped interested farmers switch to millet production.

“Malnutrition is common in this region. The results are good. We see less malnutrition, less stunting, less anemia.”

Yet millet has not yet become popular in the region.

“Hardly anyone grows millets these days,” says a villager, Ganesh. “We don’t have money to buy millet from the market,” he also says. He gets rice through public distribution, and because millet is still grown on a small scale, it is not cheap.

A kindergarten teacher is aware of the health benefits of millet, but says she does not cook it for her own family at home.

“We cook different food. Rice. For millet you need a steam cooker and a gas connection. We cannot cook millet on a wood stove. It only tastes good when it is cooked on gas.”

Introducing millets and changing people’s eating habits is a challenge, Durgalla agrees. “It has to be done slowly.”

Yet, according to gene bank director Singh, it is inevitable that millet will conquer the world. “As temperatures warm, temperate crops will move further north. Crops such as millet will take up more space in many regions, in Europe and many other countries in the Northern Hemisphere.

(For Latest Agriculture News & Updates, follow Krishak Jagat on Google News)