The targets for SDG 2 are directly relevant to all stakeholders in the field of agriculture

14 February 2022, India: With less than a decade to 2030, the world is not on track to ending world hunger and malnutrition (SDG 2), even without the COVID pandemic. The setback dealt by the pandemic has resulted in a lost decade in the world’s efforts to eradicate hunger and reduce malnourishment. In 2020, almost one in three people in the world did not have access to adequate food – an increase of 320 million people in just one year. The gender gap in moderate or severe food insecurity grew even larger, with the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity being 10% higher among women than men in 2020, compared with 6% in 2019.

The targets for SDG 2 are directly relevant to all stakeholders in the field of agriculture:

SDG 2.3 – By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment.

SDG 2.4 – By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality.

SDG 2.5 – By 2030, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional and international levels, and promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed.

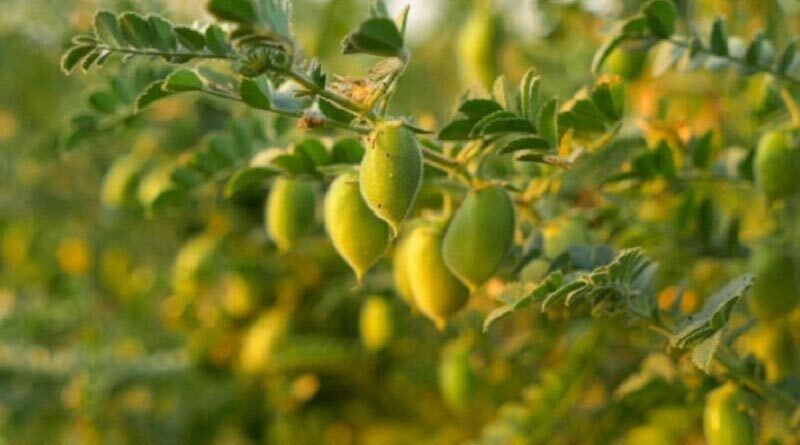

Pulses have been an essential part of the human diet for centuries. The production of beans, chickpea and lentils has been recorded as far back as 7000 – 8000 B.C. In many countries, pulses are part of the cultural heritage and are consumed on a regular, or even daily, basis. Pulses are critical to reduce the levels of malnutrition, increase diversity in the fields and on our plates, and to improve soil fertility when grown in rotation. The nitrogen-fixing properties of pulses improve soil fertility, which enhances the overall agricultural productivity. Studies have shown that the yield of rice improves by up to 20% when grown in rotation with pulses. Pulses are more water efficient than other protein sources. It takes 1,250 litres of water to produce 1 kg of pulses, compared to 4,325 litres of water to produce 1 kg of chicken and even more for mutton and beef. Pulses can be grown in the fallow seasons between the main cereal crops. Thus, they provide additional income for smallholder farmers while improving the resilience of food systems.

On the nutrition front, pulses are a key source of protein and are rich in complex carbohydrates, proteins, the B-group of vitamins, micronutrients and fibre, while having a low glycaemic index. These characteristics of pulses help manage cholesterol levels and improve digestive health. Urban populations are starting to realise the nutrition benefits, and this is fuelling an increase in the demand for pulses.

To improve the supply of pulses, inter-regional cooperation efforts in Asia, as well as Africa, can leverage the strengths of the agriculture research networks of different countries. For e.g., in Asia the ‘Seeds Without Borders’ initiative, which many SAARC member nations have joined, strengthens pulses value chains in the region for food and nutrition security. ICRISAT is proud to partner with SAARC member countries to ensure improved varieties of pulses are more readily available across the region.

To encourage the production and consumption of pulses governments, private sector and agriculture research institutes must work in a trans-disciplinary manner to achieve:

- Expansion of the area under pulses by utilizing fallow lands and reclaimed wastelands for production of pulses;

- Strengthened seed delivery systems by encouraging production and distribution of high-quality seeds;

- More Farmer-Producer Organizations (FPOs) for value addition through processing of pulses and shortening of the value chain;

- Special schemes and incentives to encourage women and youth to take up agri-business activities focused on pulses;

- Capacity building of pulse growers through the agriculture extension systems;

- Customization and development of farm equipment, including app-based hiring;

- Storage and warehousing developed in rural areas; and

- Increased consumer awareness through various media channels, including social media.

The genetic diversity of pulses held in the genebanks of ICRISAT and other institutions are an invaluable resource to develop new varieties and hybrids to help smallholder farmers fight climate change, emerging pests and diseases and other biotic and abiotic challenges. ICRISAT will continue working with all stakeholders to create nutrition-sensitive food systems by incorporating pulses in a major way in crop production systems.